Li Yongzheng on flying under the political radar

Michael Young

Whether Chinese conceptual artist Li Yongzheng (b1971) sees himself as a political artist is an interesting if somewhat moot point. In his work which ranges from performance to installation to video and open-ended participatory projects he adopts a definite political standpoint predicated on a belief in human rights and personal freedoms. But at the same time he does not express any obvious disillusionment with the Chinese government and certainly there is no radical and critical outpouring as such, no hysterical proclamatory barbs. He is far too subtle an artist for that. Nor is there any nostalgic looking back to post Cultural Revolution times which so many artists seem to want to do these days as a vehicle for their angst ridden art. Yet Yongzheng’s work remains rife with political allusions as he continues to examine – albeit covertly – several of the China’s most critical and thorny issues, human rights and personal freedom included, tropes that are never far from his thinking and which form the core of his practice. However his way of tackling these issues through oblique allusion rather than through head-on confrontation has allowed him to fly under the radar of the authorities. They simply leave him alone even though the nature of his work deals with these controversial themes.

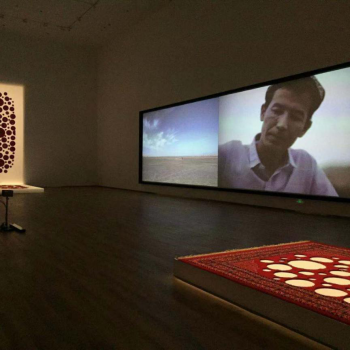

For example in October 2015 Yongzheng set off from his home in Chengdu in central Sichuan on a 3500 kilometer round trip that would take him north to Xinjiang’s Lop Nor a hostile place close to the myriad silk roads that for centuries linked Asia with the Mediterranean. Lop Nor had once been a vast inland sea. Today it is little more than marsh and salt plains pressed hard against the shifting sand dunes of the unforgiving Taklamakan desert. By any standard Lop Nor is remote, barren and inhospitable, with infinite skies that dazzle the eyes and deceives the senses. Blisteringly hot temperatures by day and subzero ones by night make Lop Nor a death trap for the unwary traveler. Not for nothing is it known colloquially as the Sea of Death.

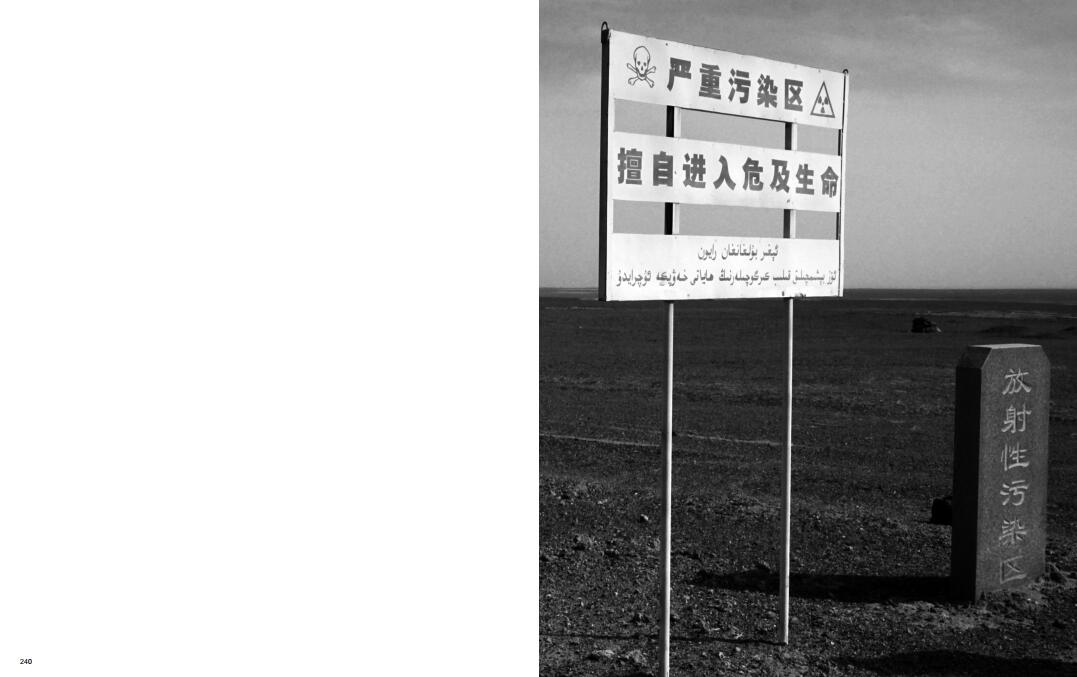

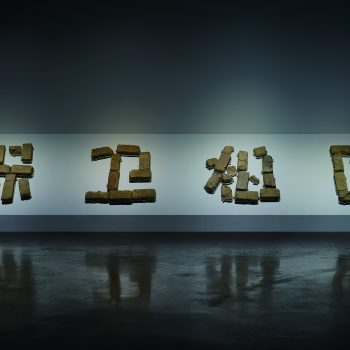

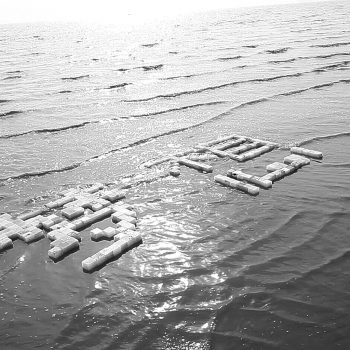

Between 1964 and 1996 Lop Nor was also the centre of the People’s Republic of China nuclear and hydrogen testing program where 64 nuclear devices were tested that drenched the landscape in a lingering shroud of potentially lethal radiation. Today near its epicenter is a disused military facility slowly crumbling into the sands. Overlooking the ruins is a one meter high by 5 meters long Mandarin character sign constructed from soft clay bricks that spells out the declamatory and xenophobic statement from the 1960s, ‘Defend Our Nation’. This was Yongzheng’s ultimate destination and once there he set about removing forty of the crumbling bricks, carefully numbering them and replacing them with new ones he had brought with him. “For me it was just about exchange in a totally desolate and different world,” Yongzheng said.

The art work that emerged from Lop Nor was Defend Our Nation, an installation, performance piece and four-channel video that runs for 15 to 30 minutes and that resonates with all the concerns that the artist has carried with him during a career that has followed a quiet yet determined trajectory since its inception in 2008; self determination, the conflict between personal empowerment and the common good, the role of the individual within society, and how to conflate the art making process and content without undermining the conceptual premise of the work. In a conversation earlier this year Yongzheng outlined his rationale behind Defend Our Nation. “I worry about a political system in which the state has substantial centralized control over social and economic affairs. The government is whipping up a feeling of xenophobia among the Chinese people with its island building in the South China Sea. In mainland China people can freely talk about this but the press can’t. All the press does is tell us that we must become a powerful and strong nation,” he said.

Defend Our Nation with its oblique reference to political hegemony and nationalism also perfectly exemplifies Yongzheng’s concern for words and actions a concept central to his practice. The work is he believes his most successful piece to date and certainly his favourite.

Yongzheng was born in 1971 in Ba Zhong a remote village ten hours by bus from Chengdu. Even though most of rural China was poor his family never really suffered because his father worked in the office that looked after the distribution of local rice production so there was always plenty of rice. This was during the closing years of the Cultural Revolution. When he was 7 years old the family moved to the city so he could attend primary school.

Yonzheng could well have ended up a writer or a philosopher judging by his interests through puberty and the dramatic growth of his cultural interests at the time which embraced literature, philosophy and the writings of Sigmund Freud the Austrian neurologist who went on to become the father of psychoanalysis. “I looked everywhere for translations of his books and bought everything I could by him,” he said. At the same time Yongzheng came under the influenced of the poet Bei Dao, leading light of the so-called Misty Poets, a nebulous group a generation older than Yongzheng that included Gu Cheng, Shu Ting, and Yang Lian.

He admired the way they were prepared to criticize the restrictions placed on art during the Cultural Revolution but in a way that was oblique and elusive rather than confrontational. Chairman Mao’s prevailing view of art was that it should serve the people rather than be concerned with the individual. The Misty Poets took a diametrically opposite view with poems that dealt with individual freedom and an artist’s commitment to society, concerns that repeatedly surface in Yongzhengs work today. “What appealed to me at that time was that few people were prepared to criticize the government but these poets did so by using metaphor,” Yongzheng said.

Bei Dao and fellow poet Mang Ke along with the activist and socially concerned Beijing based artist Huang Rui co-founded the short-lived underground literary magazine ‘Jintian’ (Today) in December 1978. The magazine was banned in 1980 and several of the founders of the Misty Poets including Bei Dao were eventually exiled after the1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

“I was very influenced by these poets. I started to write poetry at this time because it was fashionable to doso to give expression to artistic sensibility. ”

In 1988 Yongzheng started learning traditional calligraphy and sketching and the following year enrolled at oil painting classes at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. This was the first time that the idea of becoming a full time artist entered Yongzheng’s mind. His parents were always supportive of the idea and never said anything negative. He graduated in 1994 but choose not to become a full time artist. After a brief stay in Shanghai he returned to Chengdu where he opened an advertising agency with friends and became increasingly interested in western philosophy, reading Heidegger and exploring the philosophers’ ideas on personal freedom, life and death.

Business success made him financially independent and in 1994 he was able to enroll at Sichuan University where he studied sociology for four years. It was at this time that he started painting in oils again producing a body of 80 works over a ten year period 1998 – 2008 that were never exhibited. In 1999 he enrolled at Sichuan University to further study sociology.

“Painting was my passion which I could only do in the evenings,” he said. Simultaneously Yongzheng was also building a number of successful businesses that left little spare time for the world of art which he deliberately kept at a distance.

While painting was a private and personal activity what was developing within him was the idée fixe that manifested itself in 2009 when he bought 5 tons of salt and constructed the sculptural installation Salt at GanrenBoqi Mountain 2009 that referenced the sacred Tibetan mountain with its as yet unclimbed summit and which for centuries has been at the centre of Hindus and Buddhists creation myths alike as well as a place of pilgrimage. These ancient belief structures see GanrenBoqi as the axis mundi of creation, the link between heaven and earth and the centre of the universe.

What was so striking about Salt at GanrenBoqi Mountain 2009 was its profound simplicity of form. Having been sprayed with water the salt had set firm even so the gentlest of human interventions would have brought the whole edifice crashing to the ground. Inevitably the passage of time would also have the same effect. It was a wry commentary on the threat to Tibetan belief structures continually confronted by an authoritarian regime.

Salt at GanrenBoqi Mountain marked Yongzheng as a mature artist one capable of conveying complex ideas through simple forms. The work was a sophisticated and elegiac contemplation on personal freedoms that asks covertly, can mankind ever be a vehicle of free will while under the yoke of a totalitarian state?

Five years later in 2014 Yongzheng made a further iteration of the GanrenBoqi Mountain piece this time adding a further aesthetic dimension to what was already a multi-layered work. “The first 2009 work was 5 tons of normal salt and I created a mountain. I then sprayed it with water to make it disappear. In 2014 I continued this project. Tibet people say that 2014 was a special anniversary year for the mountain. I ordered 2000 salt bricks from the Himalayas. This salt has so many natural and beautiful colors from pure white to amber and I stacked the bricks in the shape of the mountain. As the exhibition proceeded I sold each brick for 100 yuan and this was just enough to cover the cost of the bricks,” he said. Gradually the mountain began to disappear as the bricks were sold especially so when the Tinjian Teda Museum bought 300 bricks in one go.

Consumed Salt and Gangren Boqie Mountain is a simple aesthetic metaphor for the fact that while people can barely live without salt the Tibetan people cannot live without GanrenBoqi Mountain or for that matter their culture which continues to be under threat. Yongzheng offers no answers to this problem and simply sees an artist’s role as highlighting such problems and creating a forum that encourages the audience to participate in an active pursuit of answers, an altogether altruistic rationale in a country where much of the population is excluded from participating in any form of debate critical of the government’s actions.

Yongzheng continued his examination of such controversial issues. With Send For You he printed several facsimile editions of the Xinhua Daily newspaper from 1938 to 1947 the period when it was the official mouthpiece of the communist party in Kuomingtang areas whch he then gave away to the public at the exhibition. His intention was to address the party’s historiography with the deliberate intention of provoking a reaction from the exhibition audience to whom he gave copies of the newspaper.

But Yongzheng’s oeuvre is not only about raising eyebrows. Over time his palette became pared down and minimalist as salt, earth, stone, water, and fire freed from their representational associations increasingly added an air of contemplative Buddhist silence to his practice. Works such as Look, Look 2013 and Moist Stele 2013 seemed to resonate with silence, stillness and a benign spirituality that added a raw edge to our contemplation of human temporality.

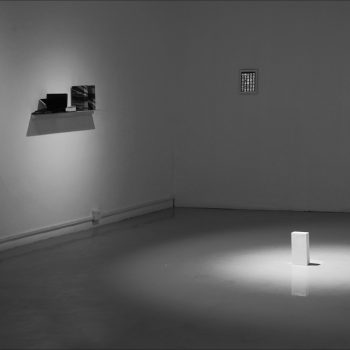

Look, Look 2013 is a half meter square stainless steel open -topped cube with four steel inner cubes all polished to a mirror brightness and then filled with water that has a translucent drum tight meniscus that stretches from edge to edge and which is only disturbed when an air bubble rises to the surface. The precise rectilinear form of Look, Look is shared with Moist Stele 2013, a great upright slab 1.8 meters tall of moist yellow sandstone from Sichuan which is either a milestone or a memento mori, depending on the viewer’s frame of mind at any given time. The stele was hollowed out and the remaining cavity filled with water. Gradually the water permeated the stele’s sandstone crust and evaporated. Both artworks riff on the temporality of human existence and convey true existential angst dressed up in unashamed aestheticism.

Both works possess a Buddhist dimension – Look, Look especially with its title drawn from a Buddhist’s texts – and Yongzheng will freely admit to appropriating certain Buddhist precepts while preferring to keep the Buddhist belief structure itself at a distance. “I am interested in Buddhist text and philosophy as indeed I am interested in many things. But I borrow the best that Buddhism offers for my work” he said.

For any socially minded or political aware artist working in China today it is inevitable that the twin bedfellows of free will and democracy will raise their heads as they did in September 2011 in the southern Chinese village of Wukan when hundreds of locals demonstrated against the sale by village officials of land for real-estate development without prior consultation or proper compensation being offered. Over the period of a few days protests developed into riots which culminated towards the end of the year with the death in police custody of a villager and the village being placed under siege. While global media reported what was going on the Chinese population could only glean a certain amount of information on what was happening through the Chinese microblogging site, Sina Weibo.

In response to the tense situation in Wukan Yongzheng made Brick Relay (2012 – ongoing) the first of his works that was to elevate the process of making the art into the work of art itself.

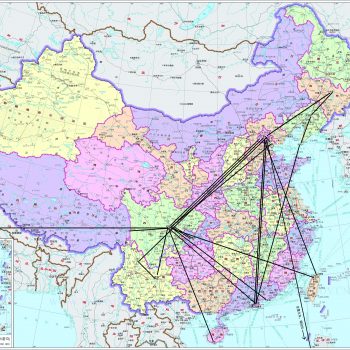

Using clay from Wukan Yongzheng made two bricks, one of which he gave to a Wukan library, and the other he mailed to volunteers on the proviso they forwarded it to friends. Participants made comments through social media and these comments Yongzheng documented as part the art work which remains an open ended project. He estimates that over one million people have so far been touched by the brick’s journey documented through Weibo and which has now reached most parts of China.

“Everyday a lot of sad things happen and people talk on Weibo so fast without having time to absorb the tragedy. I didn’t think that Wukan was the beginning of democracy in China but I do believe that it will help people pay attention to what is happened to ordinary people and their attempt to govern themselves. Brick Relay attempts to prolong the time that people can absorb this information,” Yongzhegn said.

The earth brick is still slowly travelling through China and has already been through over 100 people’s hands, the latest being the Gao Brothers Beijing artists who themselves continue to challenge authority in their work. It is Yongzheng’s intention that every time someone receives the brick they become an artist in dialogue with the work. “Many recipients display amazine creativity in the way they use the brick as an art form.Everyone is an artist and everyone is part of an inclusive democratic process with a say in the work’s eventual outcome. I believe the brick has its own destiny and my job is to record its path through the world and relay the information,” he said.

The brick has already been exhibited in several places along the way; in 2013 at a fringe event at the 55th Venice Biennial, and in a group show at Beijing’s UCCA.

Yongzheng’s adherence to the idea of an artwork’s process being as important as its outcome he also explored in Trading Secrets 2014 a work that witnessed him cut each of the eighty oil paintings produced during the 1998 – 2008 period into 9 pieces. Wearing his psychoanalytical hat he posted on Sina Weibo the following statement, ‘Anyone who sends me an email to tell a story of his own experience, in 300 words, even anonymously, will get a framed piece of work from me.’

Within one month he received 231 emails and many secrets from various people around the world and had posted out in return the equivalent number of painting fragments. “I always kept one piece from each painting for myself so if all the paintings were brought back together there would always be one piece missing, the piece I have. The work – somehow the equivalent of the psychoanalyst’s couch – stopped last year because of lack of time on Yongzheng’s part, is a platform for people to open up to talk about real things hiding inside. “Weibo blog is a huge social media site but I feel like it is very hard to get deep communication with anybody on it. Sometimes as we grow we prefer to forget things or keep them in our heart. By anonymous communication with somebody you can discover real internal truth,” he said.

For Yongzheng the artist’s role is not to provide answers to these conundrums but to frame questions addressing the problems using whatever material best elucidate their conceptual premise which in Yongzheng’s case are the fundamental elements of life, earth, air, fire and water all of which feature in his projects.

To this quartet of elemental properties create works that seductively infiltrate rather than bludgeon the viewer’s sensibilities, one could add a litany of other properties such as stillness and tranquility. Both occupy the core of every art work by Younzheng held in perfect equilibrium creating a sense of pause, a moment when reality becomes suspended.

Philosophical conceits may be rife in his work but they are held in check by Yongzhen’s intelligent use of a strong formal visual language and his humanistic concerns allowing his to produce profoundly beautifully work. His social concerns and his passion for human rights add an inevitable provocative dimension to work that continues to fly under the under the radar of government scrutiny which of course is no bad thing. To be physically engaged with works by Yongzheng is to be transported by their deceptive simplicity to a world of stillness and silent contemplation, one where art is conflated with pure human expression. “I believe we come to the world with nothing and leave with nothing. Buddhism teaches you not to fear any difficult you are confronted by and to be passionately involved with life,” he said.

In his career so far Yongzheng has arrived at a moment of inner peace. “An artist should have free will and exhibit no fear in using art to express his personal views,” he said. It is no bad creed by which to live one’s life for an artist whose works remains aesthetically pure, socially relevant and at the forefront of conceptual art in China today.

Michael Young is a visual art writer and journalist based in Sydney. He is contributing editor for Art Asia Pacific magazine, and writes regularly for Asian Art Newspaper and Artist Profile.