Li Yongzheng: Investigating Methods of Response

Text: Lan Qingwei

Li Yongzheng’s artworks engage with social issues, but I still think of him as a conceptual artist first, interventionist second. His artworks transcend ideologies. Every artist has their individual issues in which they express views on diverse subject matter and materials. We seek to discern whether artist Li Yongzheng is primarily addressing social issues, or whether these issues are a gesture within a much larger artistic expression. “How do you define something in medias res?” This is the question Li Yongzheng continually asks in his work. As he answers this question, he employs a “point of view which is still-seeing”. The point of view in question is not so much the artist’s, but a point of view being ‘accreted’ by audiences. Li Yongzheng uses this very living process as prima materia. His pieces are never merely a finished product, but tend to be material for the making of a wholly new artwork. In his creative process, Li Yongzheng transforms every artwork that’s ever ‘happened’ into new material. The artist re-uses materials in separate artworks, with water and salt as frequent motifs in his body of work. To classify Li Yongzheng’s artwork, one may reach for macrocosmic categories: Responding to Life, Historic Temperature, Social Engagement with Society, and Internet /“Games”. Artworks veer from abstraction, towards conscientious and intentional construction. Simple and concrete materials include: water, salt, metal, old paintings and the internet. Construction and assembly techniques are also simple: substitution, transformation and displacement. As with artwork Look! Look! (2013), the viewer is provoked and must respond. Li Yongzheng uses his own approach to answer life’s call. His answer is our world, itself.

Li Yongzheng dwells deeply upon water and salt. Artworks on salt include Salt at Ganren Boqi Mountain (2009), Salt on Wood (2012), Consumed Salt and Gangren Boqie Mountain, and Seized Summit (2015). Works on water include Metal as Medium for Water and Fire (2011), Moist Stele (2013), and Encounters (2014). These artworks constitute a large portion of the artist’s relatively small body of work. As he discusses (sea) water and salt, Li Yongzheng is not so much exploring these individual substances. Rather, the artist focuses on a cycle of generation and destruction. Salt is a representation of life, the sea a great body of water. But the sea expires in salt, which in turn loses itself in water. Life, death and rebirth find play in Death Has Been My Dream for a Long Time (2015), undoubtedly inspired by current social events. The artwork’s title was taken directly from a 13 year old boy’s suicide note. “Death has been my dream for a long time” explained the group suicide of four children, though this is only indirectly related to the whole artwork. Operating along a similar vein, in Consumed Salt and Gangren Boqie Mountain, the artist uses a mist machine to melt a mountain of salt. Using salt bricks from the Himalayan Mountains, the artist is emphasizing the cycle of death and rebirth, reminding us that Himalayan salt bricks source in the sea. A sea dies in a mountain. The mountain dissolves in a sea, returning into lapping waves.

We are bombarded daily with news, information pouring from mouth to mouth. What happened to snail-mail and writing letters? That was when we calmly waited for news to arrive, always waiting longer than expected. In today’s information age, we are stuck in Clockwork Orange-like onslaught, unable to process information. We strive to calm ourselves in the onslaught, to hold our sense of self amidst values forged in media-cast shadow. Be it newspaper or internet—no matter how it morphs, we must guard against information. As if written in water, ‘definitions’ proliferate. We are cast at sea and our compass is awry. Li Yongzheng explores ‘definitions’ for even utterances like ‘Hi’. It is increasingly difficult to take historic temperature in our present linguistic environment. Li Yongzheng explains about artwork Free For the Taking (Send for You) (2013) that he “hopes that we can think more about certain historical periods and fields, about problems and questions that were raised but left unsolved”. The artist freely distributes copies of Xinhua Daily newspapers re-printed on-site by an old printing machine. Information crowding out oxygen, we hold the newspaper in our hands, feeling its materiality, witnessing interwoven time stamps, asking after the artist, “Where do all the ‘unsolved problems’ go?” These unsolved problems are constantly born, dying, and reincarnating in time-stamped newspapers.

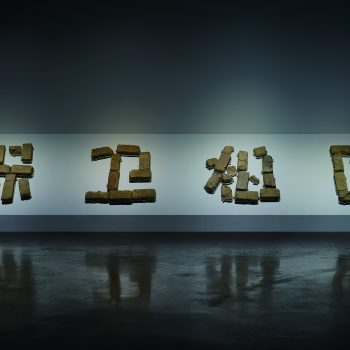

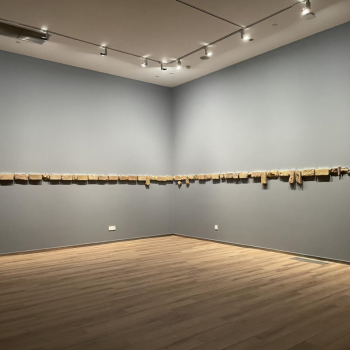

Free for the Taking followed Brick Relay (2012), the two artworks contiguous and similar in many ways. They both transmit, but in active—passive ways. Free for the Taking is an emanation of Brick Relay, an exploration of its sensibilities. Since social media, possibilities of dissemination are as numerous as people. Those involved are always closer to events than reporters, having the most sincere take on events, combining experience with feeling. News reporters are now redundant. When cell phone cameras take pictures that describe the scene more accurately than words, we still doubt what we see. Perhaps we know how adept the media are at framing a shot. Brick Relay explores post-experiences. Our account of reality morphs and resists ‘second history’. As the brick is relayed from person to person, this inquest begins anew with each transmission. The artist appears as objective and independent investigator, watching his ‘brick’ transform from hand to hand. Li Yongzheng utilizes online portals and postal mail routes to question the interaction of real and virtual spaces. Space is an old question in China, as visual artists utilize and reform spatial parities, researching images’ techne. An artwork seeks the right space to reside within, a space of contextual interpretation. Installation artworks seek ideal space, place and site for display. Brick Relay sought spaces, controlled and uncontrolled, real and virtual. Each participant found a singular expression in their contact with the brick, reconstructing and dissembling, creating new spaces. Li Yongzheng’s creative space in this work differed from others in that he set the precedent, created the program, and did constant surveillance.

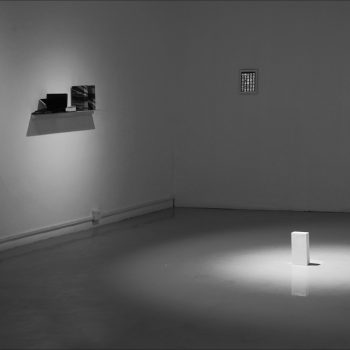

Li Yongzheng is known for his sculptures, not his paintings. We aren’t showcasing his painting, but will study his painterly technique. Life can’t be explained, but linear time tempts us to hypothesize about the past. Sorting through Li Yongzheng’s paintings, one sees a strong Western art historical influence, from classical through modern. These paintings plateau at various points along the history of art development. Hard to talk about, they are like a diary, unseen by most. Secret Exchange derives from these paintings. On May 30, 2014, Li Yongzheng also referred on Wechat and Sina to his painted works as a sort of ‘diary’, “From 1998 to 2008, painting was my personal secret. During this period of time I refrained from participation in exhibitions. I will be cutting up paintings created during this time, the smallest piece being 30 cm x 40 cm. I will sign each one.” All you had to do was send Li Yongzheng a 300 word secret, and the artist would send you one of his own secrets—a piece of his old painting. Not a profitable venture, Li Yongzheng’s insight into popular psychology earned him 231 messages within one month of the “secret exchange”, totaling 164,000 words. Extreme Cold Wave (2016) is a similar artwork, although final results are withheld in both Secret Exchange and Brick Relay. Each person involved will see the artwork as a singular node in the project. Li Yongzheng, of course, emphasizes dual processes of “relay” and “exchange” as primary. Indeed, the artist goes on in Secret Exchange to register “Secret Exchange” online. New participants exchange personal secrets for ones in the secret databank.

Brick Relay and Death Has Been My Dream for a Long Time both take initial impetus from current events and social conflict, but Brick Relay and Secret Exchange more resemble a gaming program, with social engagement within society as central mechanism. In his Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga analyzed the role of play and games in peoples’ lives, providing us with a unique perspective into Li Yongzheng’s work. Huizinga writes in chapter one, Essence and Meaning of Gaming as a Cultural Phenomenon, that “Games are superfluous. It is only when happiness provided by gaming becomes a necessity that the need for games grows urgent. Games can be postponed or interrupted. They are imbued with neither material need nor moral responsibility. They will never carry with them a sense of responsibility or duty. They are only for leisure, for playing in one’s “free time”. Only when games have a fixed cultural value—as ritual or ceremony—will they be associated with responsibility or duty.” Johan Huizinga points out important characteristics of the game. Firstly, “The game is free. It is freedom. Its second characteristic is closely related with this freedom, in that the game is different from “ordinary” or “realistic” life.” His third main point is, “The game’s time of occurring and happening are separate from ‘ordinary’ life (…) It is separate from life, with its own limitations. The game ‘performs’ its process and implications within a certain arena of simulated time and space,” Huizinga’s language when talking about aesthetic factors within the game include “intense, balance, steady, facing opposite one another, uninhibited, conflict, and resolution”. These also describe Li Yongzheng’s creative process. Both Li Yongzheng and participants in his artworks have this kind of experience, of playing a ‘game’ to mutually develop an artwork. A principle characteristic in this game is the effacement of the artist as well as the erasure of the artwork’s inception point. Li Yongzheng describes both himself and his artworks, “I seldom talk about my intention for an artwork. I set its inception point, but don’t want to limit its development or give definitive answers about the artwork. It’s an open system. If only it generates possibilities of experience and feeling, then I’m OK with it. The entirety of an artwork’s meaning is produced through interaction.

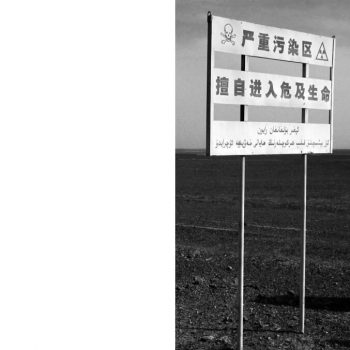

“An artwork is merely a sample.”—This is Li Yongzheng’s definition of his artwork, and Defend Our Nation (2014) is the perfection of this definition. The artwork arises spontaneously, imbued with the artist’s deep feeling for the region, environment and implications of the former nuclear testing site at Lop Nor, Xinjiang. Although many people have their own visualization of Lop Nor, few have ever visited. Li Yongzheng records his artwork on video, using new bricks to replace all old bricks spelling out, “Protect Our Nation”. In this artwork, Li Yongzheng is exchanging yet another ‘secret’. Perhaps one day in the future, Li Yongzheng will return to Lop Nor and retrieve his bricks. Or perhaps he’ll leave them to erode in the wind. Conjectures about the future are only realized in future facticity. For now, the artworks of Li Yongzheng devise ready-mades from present day reality. The artist’s newest piece Gift (2017) is similar in this way.

Artists convey social position and world identity through artwork. Although Li Yongzheng’s identity is that of ‘artist’, his artworks set him apart from most artistic production. His methods and materials, while not without precedent, gain in substance and complement through years of thinking about and implementing artworks. These works increasingly collude with one another to create what we know as the artist—an entity embedded in the artwork, set apart from the artist, himself. Artists tend to mythologize one another as artistic ‘fountainheads’, triggering and responding to each node. These myriad points of inception and response form a network of sound and response, constructing and complementing the ‘artist’. The artwork no longer stands alone. The artwork is merely a singular transformation within the artist’s overall visualization. In this mode of construction, Li Yongzheng’s modality as an artist operates in the world of information, in the realm of eternal dissemination.

Feb 9, 2017, Huangtukan, Chengdu

(Translated by Sophia Kidd)