Tian Meng: What kind of opportunity allowed you to start thinking about creating the work Border?

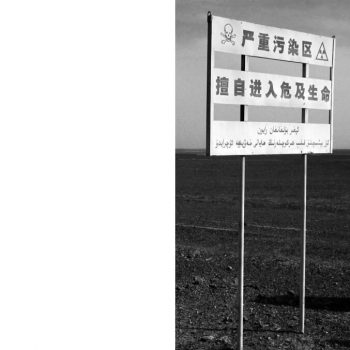

Li Yongzheng: the starting point of the Border series is the work I did in 2015, Defend Our Nation. At that time, I saw the four Chinese characters standing for the slogan: “Defend Our Nation”, i.e. Baowei zu guo, abandoned in front of a military base in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. However, I hadn’t yet fully developed a concept about works focusing on the border. Those two years were a period of strong anti-Japanese sentiment among the Chinese people, and later there was a wave of boycotting Korean Lotte products, one after another. This is also the reason why I made this work at that time. In 2017, Donald Trump was going to build a wall between Mexico and the United States. It was going to be thousands of kilometers long, just like the Great Wall built years ago in China. This made me feel very strange; I was optimistic about the methods of resolving the differences between the countries after World War II, considering that since then the European Union has provided a good model. Therefore, from one European country to another, one cannot feel the existence of borders at all. This model has put some ideals into practice and created great hopes for reducing crises. However, in recent years, the originally optimistic situation has encountered great challenges. Then there was Brexit, and the rise of global populism. After 2000, the future of global democratization predicted by Francis Fukuyama became out of reach. A border that in the past had gradually become softer, had now become harder again.

Tian Meng: Today we regard the Great Wall as a symbol of China and the Chinese nation. However, from a historical standpoint, our use of this symbol shows its absurdity. The Great Wall was historically a military fortress built against foreign enemies, and without doubts it is a border. Moreover, once the Great Wall was no more a defensive building between the enemies and us, those territories were included in the territory of today’s China. This means that the border is continuously changing and not as clear and hard as the physical building of the Great Wall. Obviously, when we use the Great Wall as a national symbol, we don’t consider the areas outside the wall and their history. When you first thought about the “border”, did you ever think about using the Great Wall as a border symbol?

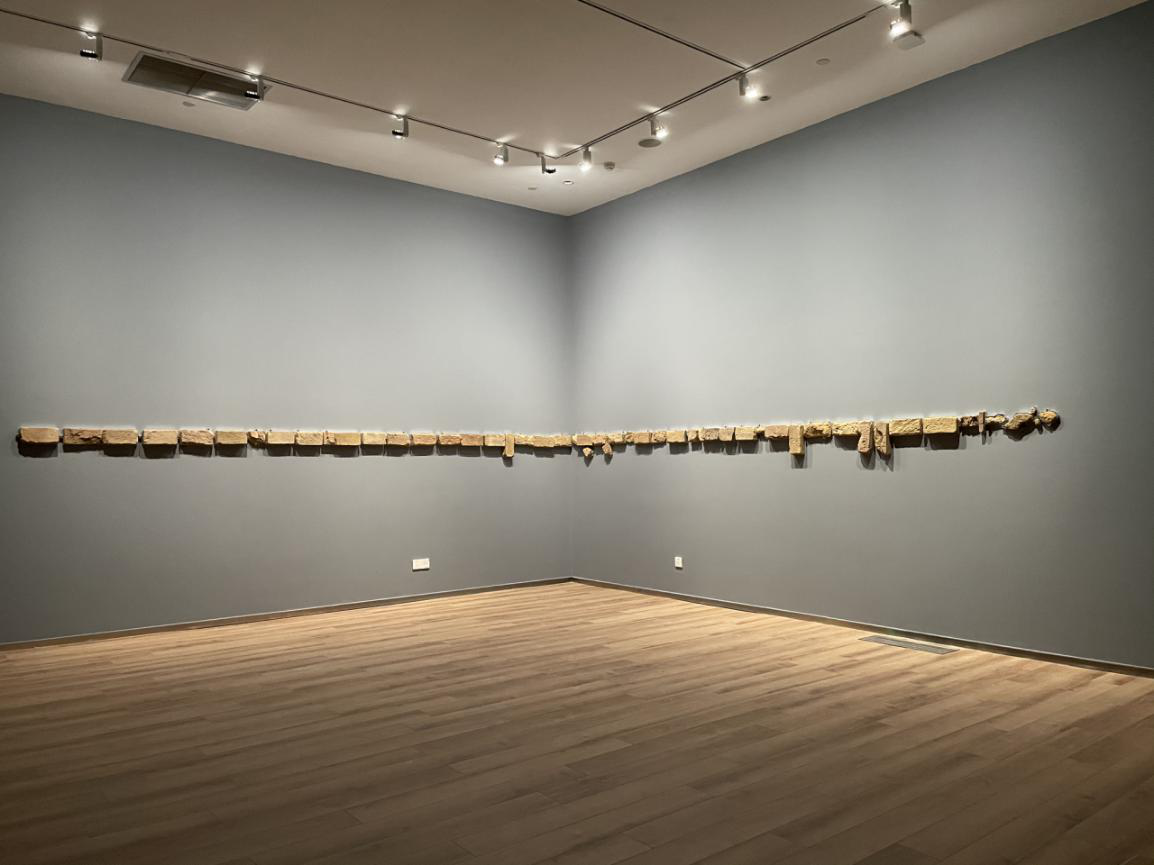

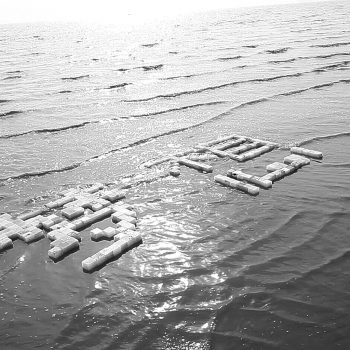

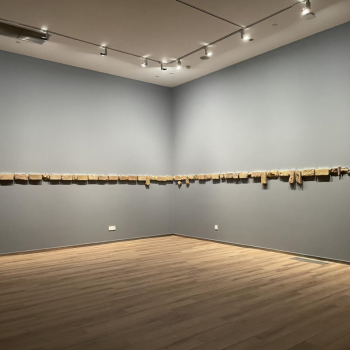

Li Yongzheng: In the winter of 2019, I made the work Border 1. Border Post which was to remove an abandoned boundary post and re-erect it 1,000 kilometers away, at the Han dynasty’s old fire beacon built in the 1st century AD, near the Great Wall. This work is the first of a series where I decided to focus on the theme of borders. The source of inspiration came from such a thought. Such a sacred and inviolable border is flexible in history, and its existence will be given new interpretations in different historical periods. In fact, any hard things will change greatly in time, although these geographical delimitations are related to many people’s recognition of honour and happiness.

Tian Meng: The Great Wall provides us with the opportunity for reflection. The concept of nation we are shaping is to a large extent dehistoricized, or shaped by a selective use of history. Someone on the internet has recently produced a video that shows the changes in China’s territory from the Shang and Zhou Dynasties over the following thousand years in just a few minutes. In a very intuitive way, this video shows that the border has always been changing. While watching this video, I was thinking: What is the legitimacy of establishing our territory or national sovereignty today? From such a perspective, we will find that different countries and nations have different understandings about the history and the present, and consequently, different understandings of borders.

Li Yongzheng: Of course, we can also say that borders are shaped by power. Just think about the source of the power legacy today: a subject of power must incorporate a mature and even consistent narrative into the consolidation of its power. Therefore, it is difficult for most people to look at the current border dilemma from a historical perspective. If you engage in some specific discussions with some people, you will discover that the standard answer is easily accepted by most people. Too many people have already lost the resources and the ability to understand the facts.

Tian Meng: In your works, you sometimes put the focus on a specific event or news, such as Death Has Been My Dream for Many Years. In fact, in a certain sense, this work expands the problem and the concept of the border, extending the visible border to various social problems, and thus explores another invisible border of consciousness.

Li Yongzheng: Yes…in the end, the border is a problem of human perception. We are influenced by some big concepts, inspired by grand narratives that are irrelevant to urgent life situations. When we talk about borders, borders are a distant concept that inspires your glory or sorrow. But in fact, the real frontier is the consequence of an individual’s perception of the world and actions based on different values. A person who is easily glorified by distant concepts often lacks the enthusiasm for solving specific problems. And in concrete reality this has meant that there are borders everywhere.

Tian Meng: Actually, this is about daily life, and the concept of border is related to what the individual meets in his own life, rather than representing an abstract and unreachable border. During the epidemic last year, you also went to the Northwest Desert to complete the work Feast. This work also involves the daily relationship between people, but this happened during the epidemic and in an uninhabited desert.

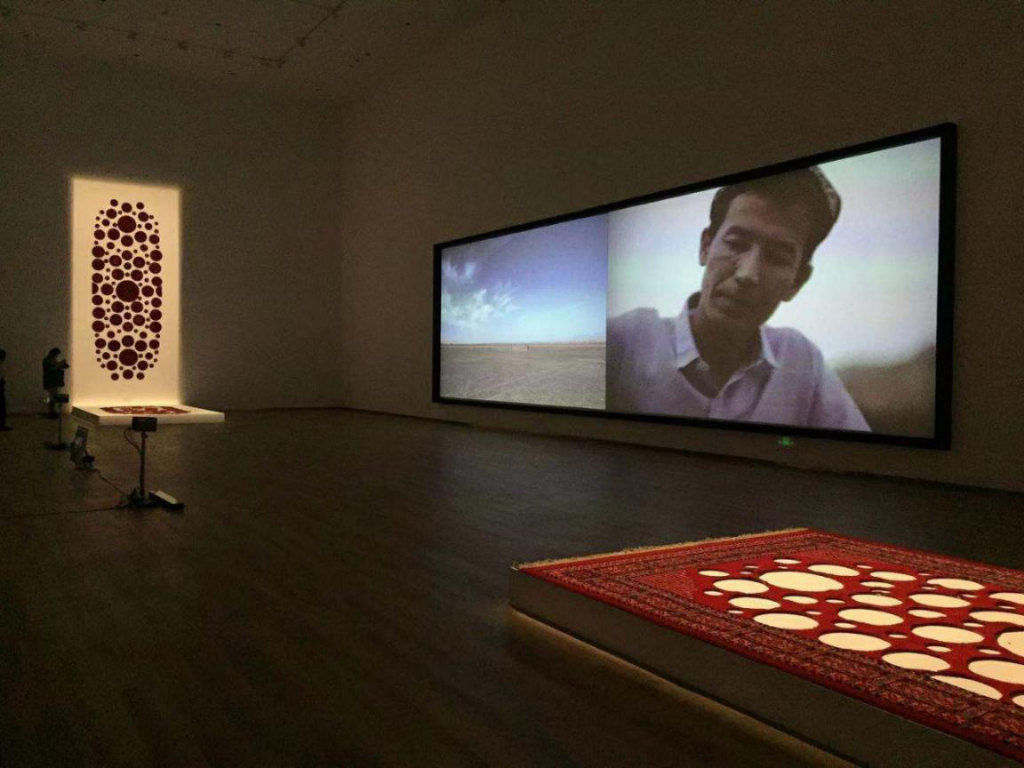

Li Yongzheng: In September 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 epidemic, we went to the desert on the north border. We invited the ethnic minorities living in the area to have dinner in the desert’s valley. I wanted to reach out through some concrete actions, hoping to fill some gaps and show some hope. When the border is not so abrupt, there must be a period of relative harmony between people, and there is an opportunity to comfort each other with words and actions. When we lose these actions, the border becomes a high wall, rising higher and higher, and it will coerce many people or many families to gradually become cold in its shadow.

Tian Meng: Why did you choose Uighurs? Why did you choose a desert, that is a place where there are no people and where there is no breath of life?

Li Yongzheng: Those people live there, in this area which is part of the vast western border. I am also relatively familiar with that place since previous works on the border were also completed there. The Lop Nur area is called the “Dead Sea” because of the drought, but these canyons are formed by the melting of the snow and ice of the Altun Mountains. The canyon is full of life and is a paradise for many animals. The desert in the canyon and above the canyon are completely different scenes. However, the desert on the gorge was once very prosperous in history. It was the most important post and trading post on the Silk Road in the Western Regions of China. It used to be a very glorious civilization, but it is silent today.

Tian Meng: Did you explain your thoughts to them when you invited them to the banquet?

Li Yongzheng: No, we commissioned local friends to be introducers. These people were their contacts. They told them that some Han friends wanted to invite them to kill sheep and cook in the desert canyon. They may have been curious, and just came. It is true that the scene made them feel something different from their daily life. In fact, it was a rare spectacle for them, and also for us. I remember a girl named Gu Li, she said, “Today is like a dream”. Yes, after driving hard in the desert for a few hours, I came to such a place and set off fireworks. Everyone sang and danced together. To them, it was an unforgettable experience because that day was so different from their daily lives, also for us.

Tian Meng: During the performance, did they show their curiosity or ask you any questions?

Li Yongzheng: We were curious about each other, but we were not very good at communicating. Maybe because they don’t speak Chinese very well, or maybe we both had concerns and couldn’t open our hearts.

Tian Meng: “Not being very good at communicating” is actually the gap between people you talk about. In such an environment, there might be a certain amount of alert between you.

Li Yongzheng: The border is just ubiquitous. I remember that during a vacation in Lijiang in 2007, I wrote a short article, defining countries with traditional sovereignty that separate themselves from other political entities through physical media as “hard-border countries”, and those using the internet to tie the community as the predecessor of the “soft-border countries”. These “soft-border countries” will form a group of common values, and they may even have common actions at some point. Although they respect the actual rules of the “hard-border countries”, other actions are guided by their community values. They even have their own currency. I think that in a few decades, the traditional concept of the country will encounter great challenges.

Tian Meng: The “soft-border countries” you describe have been forming in recent decades. From multinational corporations and globalization to the internet and Bitcoin in recent years, we have been continuously changing our understanding of the traditional concept of the national borders. For example, in the internet world, some groups are transnational and have their own existence and organisational form. The social and organizational forms of these groups are just like the concept of “soft-border countries” you mentioned. This may be the form of the future state. However, there must be new problems here.

Li Yongzheng: Humans have problems, life just can’t be perfect, and the society we build will never be. We hope that actions will change the future, but I am not an idealist, nor do I think that the future we build will be better than today. History always repeats itself, but these pessimisms can’t stop the current action. I can’t stop hoping because of fear, we exist just because we constantly create hope.

Tian Meng: In a recent conversation with some friends, I suddenly realized that some of the consensus we once thought do not actually exist. When it comes to specific social phenomena and problems, there are huge differences in cognition between people. This gap in perception prompted me to think, what caused these serious divisions? This differentiation exists between different generations, as well as between people of the same generation. Sometimes, I feel that these differences only involve common sense.

Li Yongzheng: People have an instinct to seek advantages and avoid disadvantages. If you don’t really regard a certain value as an inevitable practice in life, then you will intentionally or unintentionally adjust your words and actions according to the pressure of reality, just like it happened to some friends of mine who in the past used to share some values. For many people, such an adjustment does not even represent a conflict of ideas, because when it comes to personal advantage it is easy to find the reason for one’s consistency. We may be among those kinds of people, but the difference is that we are aware of this. So, I don’t care about what others say or what changes have been made, I am more concerned about what I think and feel at the moment. When walking alone becomes a habit, I don’t need to gain the power of action in the group.

Tian Meng: In your understanding of the “soft-border countries” and estrangement, an extremely important element involved is negotiability. This should be a characteristic of modern civilization. Contradictions and conflicts must exist in our real world. However, negotiability itself is a way to solve problems in real contradictions and conflicts. This will also soften the border to a certain extent and make it more flexible. Negotiability can, to a certain extent, place contradictions and conflicts on the level of diversity and difference and will not push contradictions and conflicts to violent disasters. This is a relatively ideal state. Of course, none of us are thorough idealists. I even feel a kind of fear among those who hold non-negotiable views. This fear is not because of their direct harm to us, but the non-negotiable argument reminds of the thoughts and concepts that led to wars and massacres in the history.

Li Yongzheng: Yes, this risk is always present, and I am not optimistic about the future either. That kind of active negotiation has never happened to the land under our feet. The advancement of technology makes what Habermas calls the “public domain” also appear to be diminished. We have never been unconsciously controlled by various information like we are today. People believe in everything they see more because of all this. It’s all what they like to see. In the political field, showing off power has become a fashion, and power has reappeared on the stage in many places without concealment. This is a dangerous signal. We have not gained experience from historical disasters. Benefits are still the most important thing in globalization, and the exchange of interests has become a weapon: it concealed many disagreements under the iceberg and suppressed the voice that we should have a possible beautiful world based on values. These results will eventually make the contradictions irreconcilable. The world is losing its foresight, and mankind can only wake up for a while after encountering a major crisis. Many times, when discussing these issues, I feel absurd, because even when talking about these topics that have nothing to do with our specific reality, I will be unconsciously cautious, so in this situation, I would rather prefer to talk about some kind of specific negotiations, like an illusion.

Tian Meng: Another phenomenon is that before we have completed our individual understanding of concepts, many people have retreated to a collective consciousness. They imagined collective unity to be merged with the individual. In the collective, the individual is abandoned, and the individual’s decision often depends on the collective choice, and also on the discourse of authority as a symbol of the collective. As a result, this has brought more new barriers, more new divisions. Since the outbreak of the epidemic, we have not produced a consistent understanding of such a big event, which could bring people back to a basic common sense. On the contrary, we have seen more unprecedented differentiation. Some people consciously defend their imaginary collective and dignity, and even ignore the facts, while those who ask questions to seek the truth are regarded as heretics. In your work 2020, you collect those singing voices in the epidemic and present them poetically through the form of a door. Have you paid attention to this phenomenon of division?

Li Yongzheng: Yes, because in the current reality, only those who appear to have correct voices can speak freely. We are used to a kind of voice that has been echoed many times in our minds during our youth, but today, when this voice suddenly becomes no longer correct to us and gradually disappears from our conversations, this is when we feel the split. When this voice speaks about real or imagined danger, then the gap of the split is wider. Personally, the year 2020 will definitely have a great impact. Just like the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake: I haven’t been able to get out of that shadow for many years. According to the method I used in the past, I would give voice to respond to such unforgettable things. The door is an interesting image that represents this, and I also like the word.

Tian Meng: When you made Defend Our Nation in 2015, did you make structural thinking about the “border”? Or did you gradually clarify your understanding of this subject in the later process?

Li Yongzheng: The idea of making a series of works about the border came into being between 2017 and 2018. Before this, it was very vague. Maybe this kind of concept has always been something I wanted to understand, but I couldn’t find the answer.

Tian Meng: In fact, you discussed this topic in depth from the perspective of the symbols, involving a historical dimension, such as in Different Kinds of Will Power where you used the symbol of the swastika. This symbol makes people have an imaginative relationship between the swastika in Buddhism and the swastika in the Nazi party. Does this mean that your thinking on the “border” issue extends to the ideological and historical dimensions?

Li Yongzheng: This symbol appeared a long time ago, six or seven thousand years ago, both the Sumerians and Aryans used this symbol. This may be some kind of illustration of their interpretation of the universe, very similar to the Chinese Tai Chi. Later it was used more in Buddhism. In Buddhism, it symbolizes light and means endless reincarnation, and it is the same concept for most Buddhist schools. But this symbol is widely known to the world because the Nazis have used it. I don’t know why they chose such a symbol. Perhaps they thought they inherited it from the ancient Aryans. The focus of my concern is not on the history of this symbol, but on the phenomenon it presents. It represents a very compassionate religion, and also reminds people of the Holocaust and concentration camps. What I am concerned about is what kind of power the content of this symbol has. Just like a theory or a social phenomenon that suddenly one day is given a new interpretation, and then erected by power to become a sample.

Tian Meng: Once knowledge becomes a tool for shaping power, then this kind of knowledge is worthy of vigilance. Power is sometimes used to cover up ill intentions in the name of knowledge or truth.

Li Yongzheng: Even under a very compassionate cultural system, once a certain kind of thought is established as an unshakable position, it is a source of danger. When a kind of thought engulfs everything, then it would definitely hurt the belief in freedom. Therefore, there is no real unshakable goodness, goodness exists only in the balance of power.

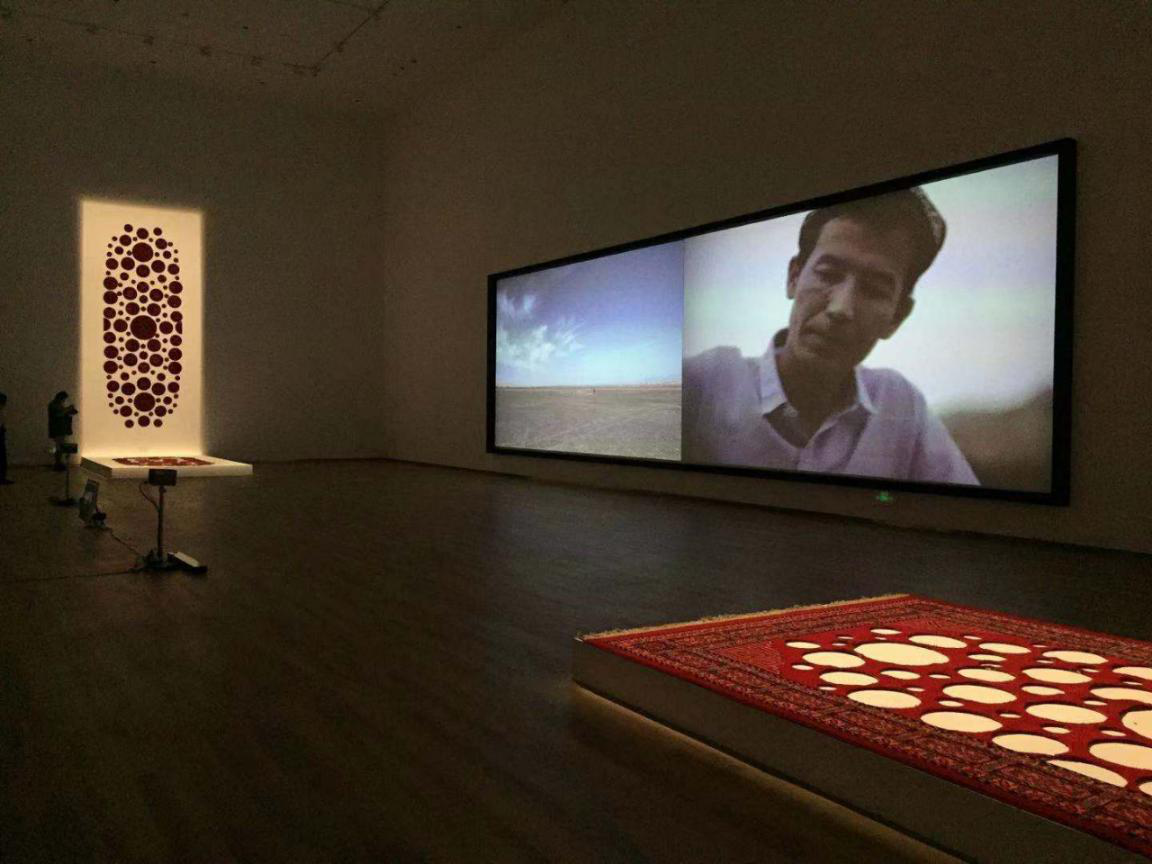

Tian Meng: In A Family from Ding’er, you used the carpet as the material of the work. Based on general experience, we would think about the relationship between carpets and Northwest China. In the work, you also pour wax on the carpet. Why in this work did you choose a carpet and wax as the materials to explore the subject of the border?

Li Yongzheng: On the border of western China, whether it is the Tibetan, Kazakh, Uighur, or Mongolian ethnicities, the most decorative objects you see in their homes are carpets. This is an item that is closely related to their lives and culture. It is a kind of “warm existence”, loaded with emotion, and a symbol of a happy life. I use wax to cover the carpets and shape them into something that expresses my emotions. In my memory, wax represents a necessity for long-term preservation of some important things, allowing some things to persist. Wax can seal the warmth that is not easy to leave at the cold border, and it has some softness that can disappear at any time without leaving a trace.

Tian Meng: In these works, you did not make a very clear judgment, but through an easy-to-access way you let the audience understand and think, and you provided them with a space for thinking.

Li Yongzheng: I never write answers, maybe I don’t even have any. I have a moral premise, but I don’t want to expose it: I just present them emotionally. It is these people and things that made me feel full of emotions. I just made a door, there are many things in here. How far the viewer can go is their business. In fact, it doesn’t matter if you see it or not. If this door makes them feel some curiosity, it is already a good result.

Tian Meng: In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera said that novels are not someone’s spokesperson, or even the author’s own spokesperson. This is consistent with your idea of creating works.

Li Yongzheng: I like Milan Kundera’s work and his mode of expression, because no matter who you are and what kind of thoughts you have, we are all within an independent survival system. If you always want to present your thoughts instead of building consensus, then your ideas are considered to be black words which can only be spoken to people who understand the code of these words, and besides, it may be more appropriate to explain them further. Another way of expressing ideas is art, which I think represents an exceptional approach, since it is the only way you can express yourself when words can’t.

Tian Meng: Milan Kundera also tried to define the characteristics of the novel itself, so as not to make the novel become a vassal of a certain philosophy or thought. In his view, novels are the discovery of the possibility of human existence.

Li Yongzheng: Art rises where language stops. I don’t like some extreme forms, or giving them too much interpretation, because no form is essential. These forms are just in the use of time, given a certain status by power, and are related to the change of power. I like to look for resources from different systems, as close as possible to the people and things related to survival, the so-called possibility of meaning will be revealed in specific people and things.

Tian Meng: You have repeatedly used salt and wax in many works. These two materials create a sense of strangeness to a certain extent, and the narrative also makes people wonder why the artist chose these materials. This may become a door that opens into your work. What is the special meaning of salt and wax to you?

Li Yongzheng: My use of salt and wax is related to childhood memories. For instance, salt was very precious during my childhood, and it was the most important reserve in the family. Without salt, it would be difficult to survive. Each of us can only use our own experience as the first step to start action. I am not against creating realistic spectacles, I believe that the aesthetic, formal, and methodological strangeness is also a very interesting part of contemporary art.

Tian Meng: Since Defend Our Nation in 2015 , the Border series has been an ongoing creation for 6 years. Are there any plans for further creations on this subject?

Li Yongzheng: Not at present. I am not the kind of person who pursues the same theme. I am always attracted by something new. Curiosity can ease my anxiety and fear about the future. Of course, I can’t rule out that I will make similar works. But in the next steps I will not focus on this aspect. I will shoot some videos to reinterpret some religious stories, and I will create in a way that is less like contemporary art. It requires action to establish the method.

April 7, 2021. Tian Meng: Curator, Art Critic, Director of Lushan Art Museum